Waiting Room: A Visual Essay on Art, Mental Health & Identity

Waiting Room: A Visual Essay on Art & Mental Health

Summary

This article offers a presentation and deconstruction of a piece of research-informed art that synthesize my practice as both an educational researcher and an artist, and as a contemporary oil painter. The argument that painting, or other forms of artistic and creative activity, can meet the academic requirements of producing and disseminating knowledge with comparable authority to text is presented first, followed by an elucidation of how one such painting, Waiting Room (Figure 1), can serve as an illustration of this endeavour, being embedded in research, synthesis of ideas and construction of argument.

Introduction

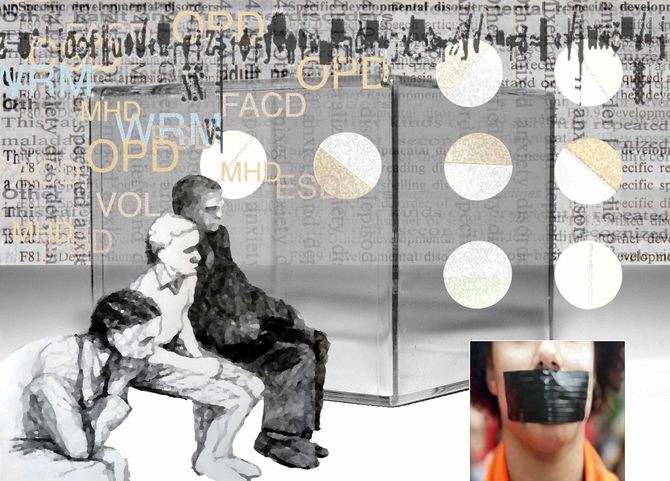

Figure 1 shows a painting, ‘Waiting Room’, completed in 2011, which visually represents my thinking in connection to a pre-selected theme/research topic: the impact of educational/medical discourse on identity. The research undertaken to inform the painting can be grouped into two categories: (1) a review of relevant literature and devices used by other artists to explore similar topics, and (2) conversations with both mental health ‘professionals’ and ‘service users’ about diagnostic ‘disorders’ and issues of mental health, as well as their views about the development of the image and its symbolic content as it progressed. Before the process of developing the image and the commentary are shared in greater detail, I will discuss how painting, and other forms of artistic practice, can be seen as activities incorporating research and dissemination, including their comparative merits and limitations to text-based approaches.

Figure 1: Waiting Room, Edward Sellman, oil and mixed media on canvas, 163×122 cm (© Edward Sellman).

Painting as Essay

The process of developing a painting, and other forms of artistic practice, involves undertaking research (Sullivan 2010). Competent artists will critically consider what message their work is to convey, how this relates to their experience and understanding of reality, and how the formal elements of their work (e.g. composition, imagery, line, space, shape, texture) can be arranged and exploited to best convey their intention. The output can be seen as a means of disseminating this research process to others. The term ‘visual essay’ has been employed to refer to one or a series of images incorporating social messages informed by research or reflection (e.g. Rose 2007; Thomson 2011), and in this article it is posited that a socially engaged painting can be understood as a visual essay on a topic.

There are several ways of thinking about what art has to offer (Carey 2005; Fischer 2010) that other outputs of research may not. None of these claim to do a better job, but rather one that is different to natural science (Vattimo 2010). Midgley (2002, 2004) poses a philosophical challenge to the authority claimed by science over the arts. She reminds us that science, including its most positivistic branch, has relied on experiences acquired through the senses to understand the world, and has often represented this visually to convey meaning. She also emphasizes the importance of meaning, critiquing science’s attempt to monopolize meaning through its exertion of stringent quality criteria pertaining to what counts as valid knowledge and epistemology. Yet, she argues that when it comes to matters more regularly concerning social scientists such as relationships, emotions and ethics, art, literature and poetry and even spirituality are far better servants of meaning and have a great deal of validity on such topics. Art therefore represents an appropriate choice for researching the impact of certain discourses on identity.

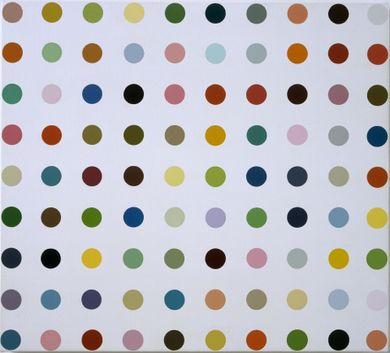

There is also Wittgenstein’s point (2001) that language is an elaborate indexing system of the physical world, represented through nouns, verbs and their relationships. Or Postman’s point (1995) that language is a technology. Words are tools indexing an element of experience, and although the written word can have a more fixed nature, its meaning is frequently affected by context and can be contested. Science’s use of language has been an attempt to fix the meaning of a word, something that art has both endorsed and challenged in the past. Art, particularly pre-modern art when general literacy levels were low, has often used its formal elements to serve a similar purpose: crucifixes, halos, the division of the picture plain into thirds, etc. have intended meanings and serve as common reference points for viewers. Even postmodern art attempts to do this in a sophisticated sense, as modern art ‘quotes’ from its own heritage and develops its own ‘in-jokes’. Much of Damian Hirst’s work (Kent 1994) can be seen in terms of reference to the Dada movement for example. Nonetheless, the meaning in such works is frequently more fluid and dialectical, allowing for subjective responses and engagement with the work.

The use of a visual metaphorical approach to ‘language’ is perhaps key to the power arts have in saying something about human experiences (Midgley 2004; Parsons 2010). People in fact struggle to convey the nature and depth of their experience in factual language. One only has to recall Wystan Hugh Auden’s poem about the death of a close friend or lover, ‘Stop All the Clocks’ (1995), and compare the meaning this would convey over the information provided by a coroner’s report or death certificate to illustrate this point. The arts use visual metaphor in a way that science would not endorse, yet the conveyance of meaning, whilst referring to the same fact in actuality (e.g. a death), is arguably much deeper and more meaningful, and therefore useful for communicating the experience of the fact (e.g. mourning), when expressed via metaphor.

Sontag (1979) and Rose (2007) draw our attention to the poignancy of the still image as another powerful vehicle for visual communication of meaning. An image can raise the viewer’s awareness of a moment in time and why this particular moment may be significant. In cases where the still image has been selected and/or composed, the viewer also has to contend with why such decisions have been made in a particular way, what they are trying to communicate and why this might be important. Given the mega visual culture we live in, and the speed of image presentation, the ‘moment’ can encourage deeper reflection as it demands the viewer to slow down and contemplate (Abbs 1988). Reflection is also needed on how the elements within an image have been juxtaposed: What, if anything, do they symbolize and what are their relationships? This encouragement to look, feel and reflect can establish a relationship and a dialogue between the viewer and the image-maker. Such an output is more consistent with a cultural theoretical standpoint that acknowledges the contextuality and shifting nature of mediated meaning. This relationship is of course possible with any style of writing, but the visual has an immediacy here, allowing complex relationships to be sensed and processed instantaneously, although their meaning may change upon subsequent and deeper reflection. Hence, time with an image such as Figure 1 may lead to a different type of ‘conversation’ than one would have with a text, such as a research report.

The Process of Researching and Making the Image

Figure 2: Compositional study for Waiting Room, Edward Sellman, photographic collage and pencil drawing (© Edward Sellman).

The process of producing the image shown in Figure 1 involved (1) consulting two areas of literature: visual methodologies and the impact of educational and medical discourse upon identity; (2) looking at the work of artists treating similar subject matter and the kinds of metaphors they use (Beveridge 2010 provides a good review); and (3) conversations with a mental health nurse and a psychotherapeutic counsellor as well as two young adults identified with a diagnostic ‘disorder’ in the past (ADHD and depression/bipolar disorder in these cases). These strands were then synthesized into a visual exploration of the topic in both preparing and executing the painting, which will be more fully explained in the commentary that follows.

In developing the image, photographic research (of figures and text) was initially conducted and Adobe Photoshop used as a virtual sketchbook. This software allows an image to be built in layers, and consequently elements of an image can be selected or deselected and moved around. The advantage of this process was that it allowed the composition to be manipulated numerous times before a strong image was achieved. In the early stages, a collage of text, a photograph of a small glass box, circles and a line drawing of figures in a waiting room were moved around (see Figure 2). There was also a blindfolded head screaming in the image, a testament to the work of Edward Munch and Francis Bacon, which was soon edited out as a less promising idea.

The early stages of the process were informed by the kind of research artists do, drawing, and playing with composition and different effects (Sullivan 2010). The sharing of early images with colleagues from mental health professions and service users was informative at this stage. Their feedback led to editing decisions, further compositional play, and the taking of further photographs to enrich the image idea before the painting stage, until it resembled the design shown in Figure 1. This iterative process served at least two functions: (1) it helped strengthen the work visually, but also (2) gives it greater credibility as the image incorporates the perspectives of others with direct experiences of the theme.

When elements of the image are presented in the following commentary, features will be juxtaposed to images of other artists’ work and a discussion of literature relevant to the topic, alongside some of the comments people made when discussing the image as it developed.

Commentary

The influence of activity theory (Cole 1996; Engestrom et al. 1999) and influential thinkers such as Foucault and Bourdieu informs the conceptualization of the relationship between the individual, the institution and wider culture shown in Figure 1. An activity theory perspective suggests that there is a weak boundary between psychology and culture, where human behaviour is mediated by culturally produced tools such as language, which in turn play a key role in identify formation. The image is concerned with how language is produced, often by powerful institutions, and the impact this has upon our values, understanding and priorities. Language is used and reproduced by individuals, often unaware of the power it exudes over their psyche (Bruner 1986).

The intellectual contribution of Foucault (1995, 2001) also informs the construction of the image. One of Foucault’s central concerns was to understand how it has come to be that people talk about certain phenomena in certain ways. In educational and medical contexts, this is usually a focus on how people have come to talk about marginalized groups in reference to polarized categories, such as healthy/sick, mad/sane and normal/dysfunctional. Such conceptual frameworks are useful to a researcher wishing to grapple with the figure in relation to context, from both an aesthetic and/or a theoretical standpoint.

Metaphors

The painting’s (or visual essay’s) main thesis is that institutions produce forms of language that exude tremendous power over the ways in which individuals understand their difficulties with social life and the options for support available to them. Hence, the development of the image sought to manipulate the formal elements so that a number of metaphors could be constructed. The following table explicates these metaphors, their intentions and their sources/influences:

Clearly, this table of metaphors concerns the image’s intentions rather than audience or critical reception. Questions about the image’s success at conveying these and other unintended messages, their stability over time, and whether any of this matters belong to a discussion beyond the scope of this particular text. The purpose of the commentary that follows is to explicate the research underpinning the development of the image, to enhance its ‘reading’, and to illustrate how painting can encapsulate and disseminate rigorous research and thinking in a manner similar to the integration of hermeneutics and aesthetics described by Pelzer-Montada (2007).

The Glass Box

Figure 3: Waiting Room

background, Edward Sellman, photographic collage (© Edward Sellman).

The image of the box is derived from a photograph of a perspex science toy superimposed onto the background of the canvas and lit in such a way as to render its appearance more like a large glass container. The compositional intention of this element was to both serve as a framing device for the figures that would occupy the foreground and tie these figures to their background. It also takes on a metaphorical meaning, perhaps representing the types of examination spaces common to institutions and hospitals in particular, and the social parameters governing such spaces.

Foucault’s influence (Foucault 1995, 2001) is apparent here. According to May (1996), Foucault’s work can be understood as a critique of the application of scientific and technical knowledge, practices of division (e.g. the sick and the healthy, mad and sane) and the means by which people turn themselves into subjects (individualization). Allan (1996) describes these processes in terms of hierarchical observation, normalization and judgment of the body and psyche. Research adopting a Foucauldian perspective hence focuses upon how the body, space and time at the micro level of analysis are routinely supervised and controlled by disciplinary forces at the macro level, best exemplified in enclosed geographical spaces such as schools, hospitals and prisons. The body in the Waiting Room (Figure 1) is consequently shown in perpetual suspense: fixed, frozen and subservient to these processes.

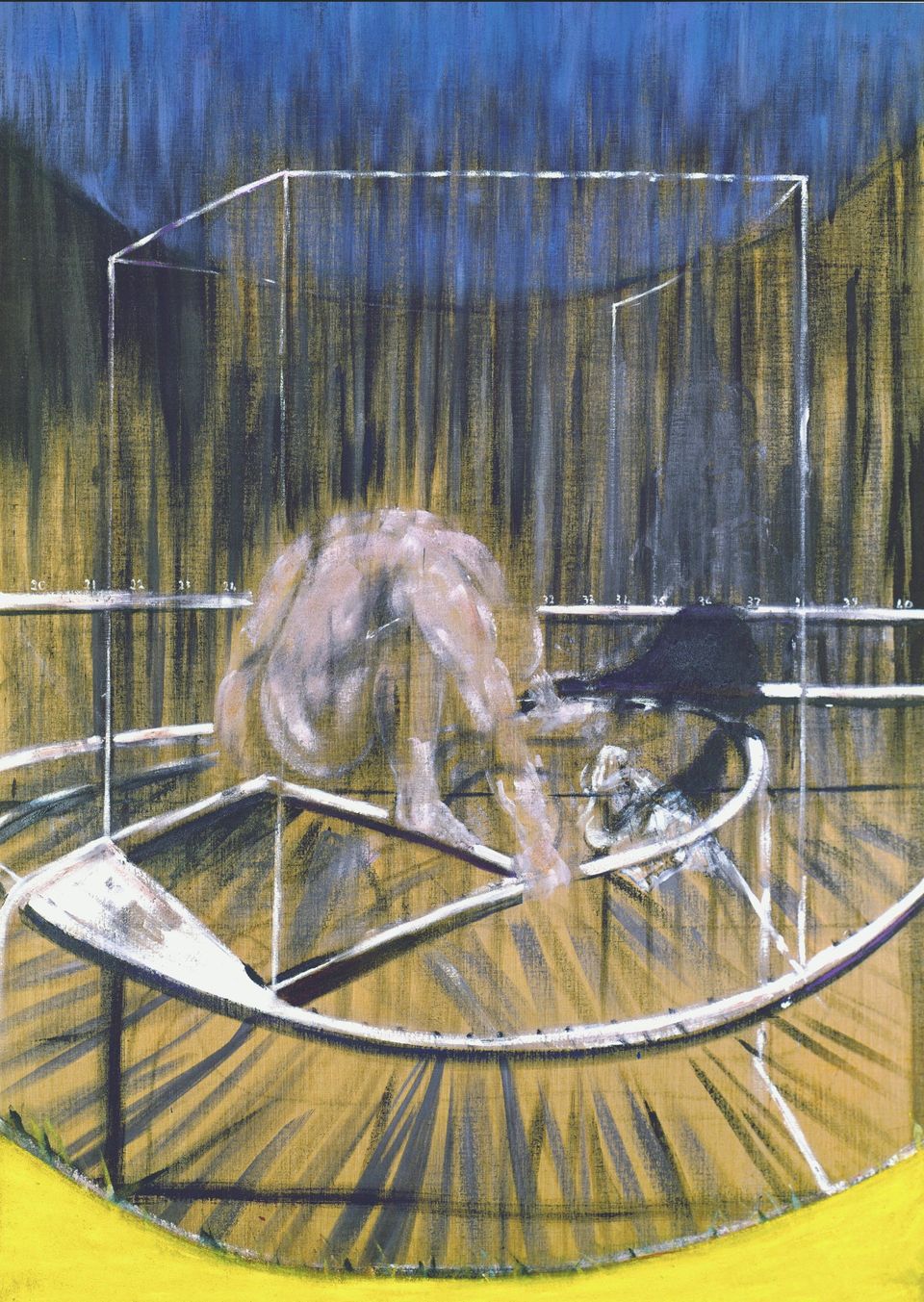

Figure 4: Untitled (Crouching Nude on Rail), Francis Bacon, 1952, oil on canvas, 193 x 137 cm

(© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS 2011. Photo credit: Hugo Maertens).

The structure of the glass box serves as a boundary between the examiner and examined, and when juxtaposed next to the text captures what Stickley and Freshwater (2009) identify as a shift in mental health practice from therapeutic spaces to those impinged upon by technical rationality (the need for objectives, observation and outcomes). It also alludes to cavities, the headspace, the body, which may also feature as the subject of an examination. Such devices have been used by artists (e.g. Francis Bacon, Figure 4) to suggest interiors but also to represent some of the social parameters and psychological spaces affecting a given space. Here, the box could stand for the clearly defined structures, roles and routines reproduced by education and health settings and the interactions taking place within. Such social parameters will be revisited when the use of tablets/halos is discussed.

Figure 5: a/b Waiting Room

details – text (© Edward Sellman).

Text

The glass box is pasted over a collage of text, originating from the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association 1994), a bulky guide used by psychiatrists, psychologists and other professionals to look up a range of behavioural characteristics in order to ascertain medical diagnoses for a multitude of conditions. Other text is also juxtaposed against this collage. A range of symbols, churned out by a computer readout, run across the top of the image, perhaps representing a medical reading or measurement. And there are a number of acronyms of what appear at first glance to be medical terms floating around the image, sometimes sliding over one another. The text was organized in this way to demonstrate the omnipresence of culture and language.

As elucidated by Bruner (1986, p. 148), the use of text in this way attempts to raise issues of power and authorship of language. He states that

...language, after all, is being reshaped by massive corporations, by police states, by those who would create an efficient European market or an invincible America living under a shield of lasers.

Seminal theorists such as Bourdieu (1984, 1991), Foucault (1995, 2001), Illich (1995) and Szasz (1974, 2007) argue that the power of medical and educational discourse is its ability to enter common parlance unquestioningly, where people reproduce discourse, unaware of the values and relationships implicit in its usage. To illustrate this point, the acronyms used in the image are completely fictitious but appear familiar. Bourdieu and Passeron (2000) have argued that when a concept has achieved power, it achieves the status of an acronym; Bourdieu (1984, p. 481) states that ‘the power to impose recognition depends on the capacity to mobilise around a name’.

In the artwork of Bacon (Domino 1996), which informs the painting’s composition, power through violence is present or suggested, and is enacted against the body through such devices as blood-red backgrounds, wrestling figures, distorted forms and jagged brushstrokes, an example of the latter being shown in Figure 4. In Waiting Room, the violence is more clinical, and is achieved through the Foucauldian mechanisms of observation, normalization and judgment, and executed by the text. The difference between Bacon’s approach and Figure 1 alludes to the shift described by Foucault (1995) from punishment of the body to that of the soul.

In Figure 1, the acronym, or the ‘name’, serves as a symbol of power – it is an apparently simple and clear reduction of complex issues into three or four letters, belying the imprecise and contested nature of the process of simplification underpinning them. One could argue that the DSM’s (American Psychiatric Association 1994) approach to representing diverse behavioural interactions, deemed to be ‘problematic’, and their complex social relationship and impact under clear headings, often achieving acronym status, is a compelling piece of abstract art. A mental health service user commented on the development of the painting to make a similar point:

There is this simplicity, certainty and austerity in the acronym, which belies the mess beneath them. Everything is separated into strands, four of these and four of these impair me across two situations – that’s it – diagnosis made. But the depiction of the text takes on this jumbled nature, takes away the verification and is more honest about the mess, the clash between the physical and social world, the over-diagnosis, technical impairments of getting a diagnosis and the different judgments drawn into a diagnosis. If it were like this, it would be a simple case of painting by numbers…

Tablets/Halos

Figure 6: Top: Pharmacy, 1992, Damien Hirst, Installation (Cabinets, glass, desk, apothecary bottles, medicine bottles, chair, fly zapper, foot stools, bowls and honey), 9ft 5 inches x 22ft 7 inches x 28ft 3 inches installation.

(© Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2011. Photo credit: Courtesy White Cube)

Bottom: Elaidic Anhydride, 2007, Damien Hirst, Household gloss on canvas, 52 x 60 in.

(© Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2011. Photo credit: Prudence Cuming Associates ).

The text is juxtaposed against ten circles, representing tablets or treatment, perhaps influenced by Hirst’s Pharmacy and paintings of coloured discs (Figure 6, see also Kent 1994). However, to some who have seen the image, they represent a divided cell, the ticking of time, or binary contrasts such as the good and bad self, the mythical or real disorder. There is some intended ambiguity here, and one must expect diverse and subjective audience interpretations. Whereas the image was created with certain intentions in mind, the psychiatric examination space could easily be exchanged for an alternative but comparable setting such as the family planning clinic. This is particularly the case if influenced by previous experience and/or if drawn to the central female figure’s clutching of her ‘embryonic’ bag (Figure 1) rather than the composition as a whole. The tablet shapes could allude to several issues, but let us discuss two here: (1) the cultural production of illness, diagnoses and medication, and (2) the ways in which the tablets also represent halos and the implications of this symbology.

There are several authors, dating back to Szasz (1974) and Illich (1995) to more recent writers such as Timini (2005), who argue that institutions such as schools and hospitals are complicit with the self-perpetuating juggernaut of capitalism in proliferating symptoms judged to be concerning, medicalized labels to organize these symptoms, and increased forms of treatment. There is little doubt that considerable amounts of money are being made from increased levels of medication, as well as a greater number of professional careers and industries needed to deliver them. For these writers, there has been a considerable shift from religious figures of authority to technical and medical figures.

Returning momentarily to the use of text, this could be interpreted as choice in the medical market. For one of the mental health service users commenting on the development of the image, his visits to the psychiatrist were not about determining whether or not he had ‘Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (AD-HD), but rather about seeing ‘what’ he’d ‘got’. He was offered ‘Obsessive Compulsive Disorder’ (OCD) and Asperger’s syndrome before a diagnosis of AD-HD was finally settled upon. His difficulties, or more likely difficulties encountered in the classroom as a result of the impact of his behaviour, had already been identified, and an appropriate label needed to be assigned. Here, the functionality of the individual rather than the context is problematized and adjudged abnormal (Thomas and Glenny 2000), something Foucault (Allan 1996) was keen to warn against, and discussed further at the end of this section.

The tablets were included in the image to remind us of choices, but also to highlight the ethical issues of health and medication, especially amid concern over the overuse of medication for such conditions as AD-HD, depression and bipolar disorder (Bailey 2009; Lloyd et al. 2006; Timini 2005). The way one tablet halos the central figure (Figure 7) was a deliberate homily to religious art, also strengthened by the manner in which the central figure grasps her handbag much like a mother would hold her infant, as previously discussed. The same user previously cited in this section also talked about the religious metaphor of visiting the health professional that is evoked by the image, also aided by the metaphorical use of the glass box.

The box reminds me of visibility, a panoptical, going inside something like a glass box and making yourself visible – in that kind of confessional way. People subject themselves to this intentionally, aware of this outward visibility, looking in on you. I think this can be really dangerous, it seems like people go and make confessions to people like psychiatrists and doctors in the interests of enabling themselves to do something better or suppressing some part of themselves they don’t like.

The image then perhaps testifies to changing relationships between individuals, religious figures and health professionals. Returning to the box, when positioned against other elements (especially the tablet shapes); it begins to resemble a confessional space, which could be entered for spiritual cleansing. Hence, the type of waiting in this waiting room is existential, potentially metaphysical, accompanied by the expectancy of adjudication. In this case, however, it is the medical explanation of why aspects of their behaviour are socially problematic that washes away the ‘sin’ of culpability, and the prescription of medication able to moderate these effects that allows them to return to their community anew. Here, acronyms are absolution.

In such relationships, the validity of the terms of reference (diagnostic criteria) and power relationships between individuals (the ‘sick’ person and the clinician) is reproduced and further self-perpetuated. The diagnosis satisfies a capitalist craving for a quick-fix that smoothes over the cracks of deeply rooted cultural problems by pacifying the individual. Under such a lens, the red and white shirt of the figure in the foreground smacks of institutionalization. Any diagnosis made continues to reinforce the role of the psychiatrist, embodied only in this image through the form of text, as unquestioned, unchallenged and ethical practitioner. This is quasi-religious role akin to the absolver of sins, in which one should diagnose and prescribe because this is what the individual seeks and apparently needs, and where a lack of diagnosis would be a denial of resources.

In considering the overemphasis on the individual as opposed to the institutional or cultural, Armstrong (2006, p. 34) describes children ‘diagnosed’ with such disorders as ‘the canaries in today’s noxious climate, […] responding in a natural way to the social conditions of the times’. The relationship between diagnostician and patient and the process of diagnosis itself detract attention from cultural and institutional critique, further contributing to discourses that label individuals abnormal, in deficit rather than just different, and in ‘need’ (Thomas and Glenny 2000; Visser and Jehan 2009). Institutional structures meanwhile are seen as fixed, natural, normal and unproblematic. And it is in such a quandary that these figures wait, trapped.

References

Abbs, P. (1988), A. is for Aesthetic: Essays on Creative and Aesthetic Education, London: Falmer Press.

Allan, J. (1996), ‘Foucault and special educational needs: A “box of tools” for analysing children’s experiences of mainstreaming’, Disability & Society, 11:2, pp. 219–34.

American Psychiatric Association (1994), The Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV TR, New York: American Psychiatric Inc.

Armstrong, T. (2006), ‘Canaries in the coal mine: The symptoms of children labelled “ADHD” as biocultural feedback’, in G. Lloyd, J. Stead and D. Cohen (eds), Critical New Perspectives on ADHD, London: Routledge, pp. 34-44.

Auden, W. H. (1995), As I Walked Out One Evening: Songs, Ballads, Lullabies, Limericks and Other Light Verse, London: Faber & Faber.

Bailey, S. (2009), ‘Producing ADHD: An Ethnographic Study of Behavioural Discourses of Early Childhood’, Ph.D. thesis, Nottingham: University of Nottingham.

Bernstein, B. (2000), Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity, London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Beveridge, A. (2010), ‘A brief history of psychiatry through the arts’, in V. Tischler (ed.), Mental Health, Psychiatry and the Arts, Abingdon: Radcliffe Publishing, pp. 11-24.

Bourdieu, P. (1984), Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bourdieu, P. (1991), Language and Symbolic Power, Oxford: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. & Passeron, J. (2000), Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, London: Sage.

Bruner, J. S. (1986), Actual Minds Possible Worlds, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carey, J. (2005), What Good are the Arts?, London: Faber & Faber.

Cole, M. (1996), Cultural Psychology, Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Cohen, D. (1994), ‘Three young artists’, Modern Painters, 7:1, pp. 88–90.

Domino, C. (1996), Francis Bacon: Retrospective, Paris: Beaux Arts.

Engestrom, Y., Miettinen, R. and Punamaki, R. L. (Eds.) (1999), Perspectives on Activity Theory, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fischer, E. (2010), The Necessity of Art, London: Verso.

Foucault, M. (1995), Discipline and Punish, New York: Vintage.

Foucault, M. (2001), Madness and Civilisation, London: Routledge.

Hartmann, T. (2003), The Edison Gene: ADHD and the Gift of the Hunter Child, Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.

Illich, I. (1995), Limits to Medicine – Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health, London: Marion Boyars.

Kent, S. (1994), Shark Infested Waters: The Saatchi Collection of Britsh Art in the 90s, London: Zwemmer.

Lloyd, G., Stead, J. and Cohen, D. (eds) (2006), Critical New Perspectives on ADHD, London: Routledge.

May, T. (1996), Situating Social Theory, London: Buckingham: Open University Press.

Midgley, M. (2002), Evolution as a Religion, London: Routledge.

Midgley, M. (2004), The Myths We Live By, London: Routledge.

Parsons, M. (2010), ‘Interpreting art through metaphors’, International Journal of Art & Design Education, 29:3, pp. 228–35.

Pelzer-Montada, R. (2007), ‘Post-production or how pictures come to life or play dead’, Journal of Visual Arts Practice, 6:3, pp. 229–43.

Postman, N. (1995), Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology, London: Vintage.

Rose, G. (2007), Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials, London: Sage.

Sontag, S. (1979), On Photography, London: Penguin.

Stickley, T. & Freshwater, D. (2009), ‘The concept of space in the context of the therapeutic relationship’, Mental Health and Practice, 12:6, pp. 28–30.

Sullivan, G. (2010), Art Practice as Research: Inquiry in Visual Arts, London: Sage.

Szasz, T. S. (1974), The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct, New York: Harper Perennial.

Szasz, T. S. (2007), The Medicalization of Everyday Life: Selected Essays, New York: Syracuse University Press.

Thomas, G. & Glenny, G. (2000), ‘Emotional and behavioural difficulties: Bogus needs in a false category’, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 21:3, pp. 283–98.

Thomson, P. (2011), ‘When only the visual will do’, in P. Thomson and J. Sefton-Green (eds), Researching Creative Learning: Methods and Issues, London: Routledge, pp. 104-112.

Timini, S. (2005), Naughty Boys: Anti-Social Behaviour, ADHD and the Role of Culture, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wittgenstein, L. (2001), Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, London: Routledge.

Vattimo, G. (2010), Art’s Claim to Truth, New York: Columbia University Press.

Visser, J. & Jehan, Z. (2009), ‘ADHD: a scientific fact or a factual opinion? A critique of the veracity of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder’, Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 14:2, pp. 127–40.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978), Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Process, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

This text was originally published in the Journal of Visual Arts Practice, available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1386/jvap.10.3.275_1

This text has been updated and reformatted in 2020. To cite the original article, please use the following format:

Sellman, E. (2012). Waiting Room: exploring the impact of medical and educational discourse on identity through painting. Journal of Visual Arts Practice. 10(3), 275-289. DOI: 10.1386/jvap.10.3.275_1